Trending Now

Caring for Our Collections: The Custodian and The Environment

Contributor: Cyndi Koh, Manager, Collections Team, Defence Collective Singapore

The Custodian – Collections Management

In the intricate world of museum operations, the role of Collections Managers often finds itself shrouded in misconceptions. Mistaken for curators or conservators, Collections Managers frequently get asked: what exactly do we do? Well, let’s illuminate that mystery.

Collections Management as a scope encompasses a wide array of tasks essential for the preservation of artefacts. This includes registering artefacts into the collection, documenting and cataloguing them methodically, painstakingly maintaining artefact records within the collections management system, and physically caring for the artefacts. While curators focus on crafting narratives and conceptualising exhibitions, Collections Managers ensure that the artefacts are safe from ten agents of deterioration (Canadian Conservation Institute, 2017) during their public display for enjoyment and education.

Ensuring the safety of the environment where artefacts are stored or exhibited is paramount and controlling physical access to artefacts is a delicate balance; it’s a privilege granted only to those who understand the responsibility it entails. Collections Managers keep a vigilant eye on the condition of artefacts, promptly alerting conservators when signs of deterioration appear on an artefact. Depending on the resources available, Collections Managers may also be tasked with drafting policies and implementing procedures to fortify the protection of the collections – at times causing inconvenience to colleagues from other departments but always with the preservation of heritage in mind.

Collections Managers are the ones who eagerly set up dataloggers to monitor environmental conditions, obsessing over relative humidity and lux levels. They carefully photograph every crack, chip, tear, and scratch on an artefact, ensuring its condition is thoroughly documented. They explore every nook and cranny of a display case and storage environment, requesting for pest traps to monitor and catch signs of infestation. They relentlessly seek the artefact’s provenance whilst at the same time fret over the artefact’s packing and storage.

In short, collections management isn’t just a job; it’s a passionate dedication. Collections Managers are wired to protect and cherish these treasures that are related to our shared heritage and wouldn’t have it any other way.

The Environment – Relative Humidity and Mould

Now that there is a clearer picture of the Collections Manager’s role, let’s delve into one of their many obsessions – environmental monitoring. Frequently, Collections Managers can be found where the artefacts are stored, as this is where most of the work takes place.

To better illustrate the importance of environmental monitoring, let’s think of an artefact’s environment as its home. Consider how Homo sapiens would prefer their living conditions – would it be a space that’s warm, damp, stale, dusty, and dimly lit. If that’s not an ideal living situation for any being, then it’s certainly not suitable for housing artefacts either.

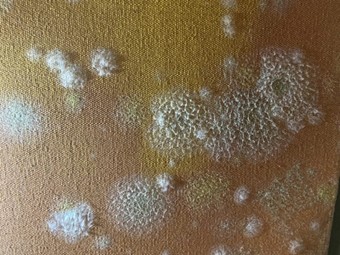

Figure (1) Visible mould growth

Source: How to Save Your Art from Mould_Stella Art Conservation, LLC

Our Geographical Location

Nestled near the equator, Singapore enjoys a tropical climate, where rainfall is abundant. The island experiences an average of 171 rainy days per year, with a total precipitation of around 2113.3mm. This climate brings consistently high temperatures and humidity levels that typically hover around 82%. However, during extended rainy periods, humidity can soar to 100%. (Meteorological Service Singapore, n.d.)

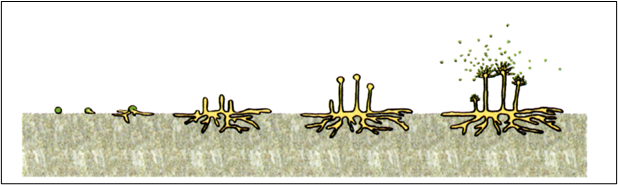

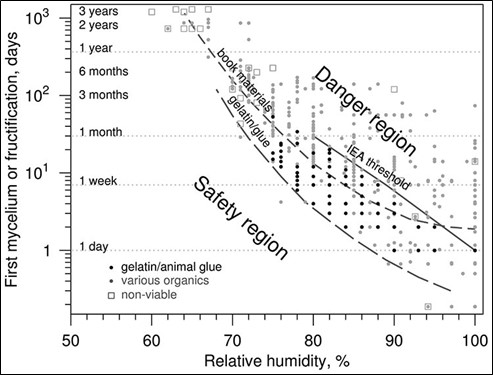

According to research findings, mould growth becomes visible within a short span of 2-3 days when relative humidity (RH) reaches 100%. The duration extends to approximately a week at 90% RH, two weeks at 80% RH, 3-4 months at 70% RH, and remarkably around 3 years at 65% RH. (Rika Kigawa, 2010) Supporting this, Figure (3) is a graphical representation illustrating the time required for visible mould growth. The x-axis spans relative humidity levels from 50% to 100%, while the y-axis represents the onset of mould growth in days, ranging from under a day to three years. (MacDonald, 2004) Considering these facts, it’s crucial to maintain indoor relative humidity below 60% to prevent mould growth.

Figure (3) A graphical representation illustrating the time required for visible mould growth.

Risks of Storing Artefacts in Environment with High Humidity

Take a photographic artefact for example, when it is stored in an environment with high humidity, gelatin which is a protein derived from animal collagen starts to soften. This can result in a few outcomes; the photograph sticking to the surface it comes in contact, the softened animal collagen becomes an attractive food source for mould growth, and the high humidity in the environment facilitates the spore germination. (Hill, 2018)

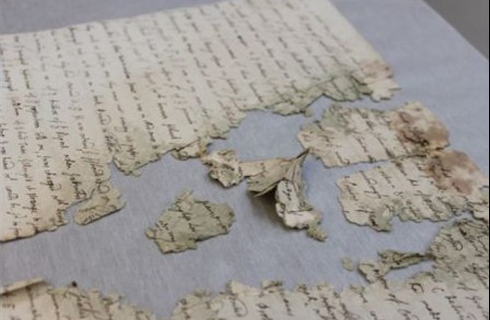

Mould poses a threat not only to photographs but also to a wide array of paper-based artefacts, including books, historical documents such as letters, journals, maps, and newspapers, works of art like drawings, sketches, paintings, and posters, as well as ephemera such as tickets, invitation cards, and menus. By inhabiting the surface of these artefacts, mould can cause permanent discolouration, and stains, and weaken the paper’s structure making it prone to tearing and crumbling. Paper’s hygroscopic nature allows it to absorb and release moisture from the environment, leading the material to swell, warp, and distort over time as shown in Figure (4) below.

Figure (4) Following water damage, the manuscript developed mould infestation. The paper’s fibres have been softened and weakened by the mould’s consumption and the image exhibits remnants of its past affliction. Source: Conserving a Mould Damaged Iron Gall Ink Manuscript_British Library Board

Textiles made from cellulosic fibres such as cotton, linen, wool, and silk exhibit hygroscopic properties, meaning they readily absorb and release moisture (Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, 2023) making them susceptible to mould growth. As discussed above, mould spores are always present in the air and require favourable environmental condition for germination and growth. Therefore, an environment with high moisture levels and the presence of food source foster mould growth, leading to infestation and artefact damage such as staining, weakening, or complete destruction of fibres as moulds digest the substrate they grow on. (Canadian Conservation Institute Textile Lab, 1996)

Fluctuations in humidity levels cause materials to expand and contract as they absorb or release moisture, potentially resulting in damage. For example, when the pigment and binder in the painted design of a silk banner do not expand and contract at the same rate as the fibres in the silk fabric, this mismatch in expansion and contraction rates can lead to the cracking and flaking of the paint layer. (American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works , n.d.)

Conclusion

In conclusion, Singapore’s unique tropical climate, marked by abundant rainfall and high humidity levels, coupled with the Defence Collective Singapore’s commitment to pioneering sustainable energy initiatives within museum operations, presents both formidable challenges and invigorating prospects for the Collections Management team to reimagine our approach to preventive conservation.

As stewards of our defence heritage and as individuals navigating an ever-evolving climate, we are compelled to embrace innovative perspectives and unconventional solutions. By fostering a collective understanding of the complex interplay between environmental humidity, the catalysts for mould proliferation, and the principles of artefact preservation, we strive to chart new avenues of exploration, ignite meaningful discourse, and cultivate impactful partnerships. Through these endeavours, we aim to empower Collections Managers in safeguarding our artefacts—our invaluable collections, our shared legacy—while concurrently minimising our ecological footprint.

References

- American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works . (n.d.). Caring for Your Treasures. A Guide for Cleaning, Storing, Displaying, Handling, and Protecting Your Personal Heritage Textile. Retrieved from https://www.culturalheritage.org/docs/default-source/resources/outreach/caring-for-your-treasures-textiles.pdf?sfvrsn=399c3869_5

- Barbara, S. (2021, May 10). How To Save Your Art From Mold. Retrieved from Stella Art Conservation, LLC: https://stellaartconservation.com/how-to-save-your-art-from-mold/

- Brewer, J. M. (2007, August ). Mold: Prevention Of Growth In Museum Collections. Retrieved from National Park Service: https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/03-04.pdf

- British Library, Collection Care. (2013, August 08). Behind the Scenes with Our Conservators and Scientists. Retrieved from https://blogs.bl.uk/collectioncare/2013/08/conserving-a-mould-damaged-iron-gall-ink-manuscript.html

- Canadian Conservation Institute. (2017). Agents of Deterioration. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/agents-deterioration.html

- Canadian Conservation Institute Textile Lab. (1996). Mould Growth on Textiles – Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) Notes 13/15. CCI Note 13/15 is part of CCI Notes Series 13 (Textiles and Fibres). Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/conservation-preservation-publications/canadian-conservation-institute-notes/mould-growth-textiles.html

- Hill, G. (2018). Caring for photographic materials. Retrieved from Canadian Conservation Institute: https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/preventive-conservation/guidelines-collections/photographic-materials.html#a5f

- MacDonald, S. G. (2004). Mould Prevention and Collection Recovery: Guidelines for Heritage Collections – Technical Bulletin 26. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/conservation-preservation-publications/technical-bulletins/mould-prevention-collection-recovery.html#a3ae

- Meteorological Service Singapore. (n.d.). Climate of Singapore. Retrieved from http://www.weather.gov.sg/climate-climate-of-singapore/

- Price, L. O. (1996). Managing a Mold Invasion: Guidelines for Disaster Response. Retrieved from Conservation Centre for Art and Historic Artifacts: http://www.museumtextiles.com/uploads/7/8/9/0/7890082/managing_a_mold_invasion.pdf

- Rika Kigawa, H. M. (2010). Control of Mould in Museum Environments: Basic Strategies. Retrieved from National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo. Japan Center for lntemationaI Cooperation in Conservation.: https://www.tobunken.go.jp/japanese/ipm-list/com/com-e/files/downloads/com-e.pdf

- Smith, I. M. (2017). Mould. Retrieved from Western Australian Museum: https://manual.museum.wa.gov.au/conservation-and-care-collections-2017/mould-and-insect-attack-collections/mould/index.html

- Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute. (2023, September). Mold and Mildew on Textiles. Retrieved from https://mci.si.edu/mold-and-mildew-textiles

- State Library Victoria. (n.d.). Dealing with Mould. Retrieved from https://www.slv.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/Dealing%20with%20mould_0.pdf