Trending Now

War Memorials: All the Glories, but None of the Issues of War?

Contributor: Jeremy Wong, Executive, Curatorial Team, Defence Collective Singapore

Regardless of one’s feelings on war, it is an event that significantly impacts people on individual, cultural, societal, and environmental levels. Thus, it is not surprising that war is remembered around the world through different forms of war memorials from educational exhibition spaces to large artistic structures with various meanings including remembering heroic individuals or important battles. Although war memorials honour those killed in war, these institutions’ commemorative natures mean that certain aspects or individuals are favoured over the other for arguably political and ideological reasons. Because of their tangible nature, war monuments can attain greater claims to authenticity and what is seemingly meaningful and worthwhile about wars.i Through their representation, these war memorials consequently decide what should be remembered from military conflicts, influencing present and future generations. These effects can be both noticeable and subtle as war memorials tend to be associated with one-way communication and thoughtful respect as proper behaviour.ii Therefore, it is worthwhile to consider how specific designs, emphases and exclusions in war memorials can influence the interests and perceptions of wars for different people.

This article will begin with examining the purposes and scopes of war memorials as a starting point to consider whether the investigated structures and institutions achieve or neglect such intentions and responsibilities. Thereafter, the methods and possible reasons on how and why not all wars, events nor combatants’ perspectives are reflected in many war monuments despite their contemplative aims will be explored. Afterwards, the potential problems of the focus on commemorations and individualised identifications of combatants will be detailed. The next section will examine the possible methods and reasons on why war is glorified in numerous war memorials. The article will then investigate how war monuments are tied up with the interests of the living despite intentions to honour and remember the war dead.

The historical and traditional roles of war memorials were to preserve and represent memories of past military conflicts for the present and future. These monuments were designed not only for commemoration, but to serve as warnings and reminders of the causes of the memorialised events and wars.iii Traditionally, monuments are conceptualised to represent a particular idea or memory that would not be altered by time and change.iv War memorials are intended and charged to offer comfort, peace, strength, and serenity to visitors.v This reflects how war memorials and monuments can be used for both commemorative and mourning purposes such as how a statue can be a testament to both heroism and individual loss.vi War memorials are also intended to provide conditions for new responses and interpretations to remembered events by succeeding generations.vii These aspects of remembrances, tributes and mourning are mostly well-intentioned, but do not necessarily co-exist in a balanced manner in war monuments. Specific text, visual and design features or approaches of war memorials can result in greater attention to one or certain aspects of war over others.

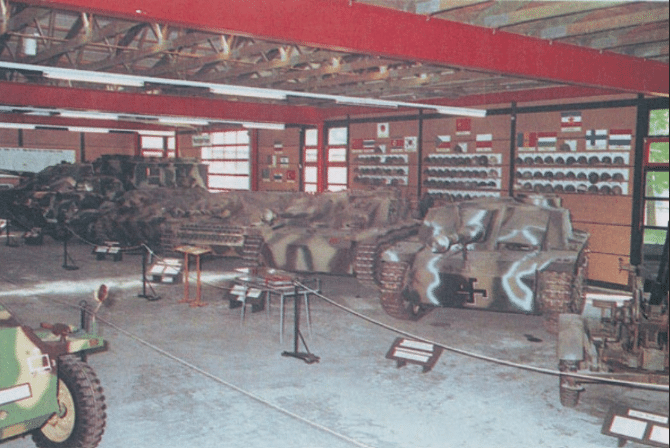

Strategies and approaches in war memorials can result in selective attention to particular views of war. The textual elements and presentation of fully restored tanks in the German Tank Museum in Munster, Germany from the 1980s to early 2000s as seen in figure 1 has arguably led to the dominance of the operational and technical aspects of tanks for visitors.viii However, this can result in fetishisation or unreasonable amount of importance assigned to these mechanical elements of war machines, rather than questions or considerations on the impact of these machines’ killing capabilities.ix

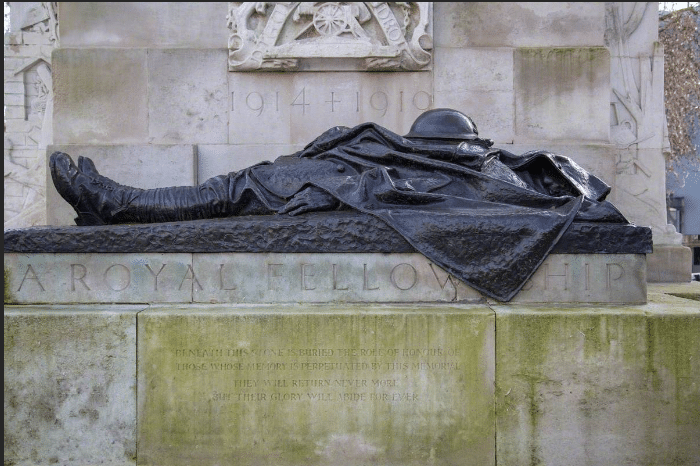

Another point of contention in war memorials is the question of the appropriateness of depictions of the complicated and violent facets of war like enemies and violent consequences in spaces that are meant for honouring and mourning the war dead. This debate is evident in the negative reactions to British sculptor Charles Sargeant Jagger’s inclusion of a dead soldier in the Royal Artillery Memorial in Hyde Park, London visible in figure 2, which was deemed too realistic and violent from other World War I (WWI) memorials in the UK.x The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. initially did not feature much about Adolf Hitler, the Nazis and World War II (WWII) due to fears that the site could become a place of homage for neo-Nazi followers to leave flowers and offerings.xi

Eventually this was changed to include a portrait of Hitler and a large Nuremberg flag reflective of the Nazis’ power base to avoid misperceptions that an unknown force caused the Holocaust.xii

The various reactions and considerations for the Royal Artillery Memorial and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum likely reflect a lack of consensus on how to incorporate sensitive aspects of war into memorial institutions and whether such memorials can fully accomplish various educational, mourning and commemorative purposes.

Furthermore, the absence of unanimous views on war memorials’ purposes and boundaries mean that these monuments and organisations can fulfil their intentions through glorifying, criticising or simplifying conflicts, participants and related events. These decisions on what to represent about conflicts in war memorials are manifestations of different political, ideological, social and cultural views.xiii

Through recognitions of these various influences and agendas on war memorials, discussions and debates about war memorials and memorialised conflicts can be maintained.xiv

Figure 1. Exhibition of Wehrmacht Tank Destroyers in German Tank Museum. ca. 1990s. Photograph. In Ralf Raths, “From Technical Showroom to Full-fledged Museum: The German Tank Museum Munster,” in Does War Belong in Museums? The Representation of Violence in Exhibitions, ed. Wolfgang Muchitsch (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2013), 87.

Figure 2. Close-Up of Dead Soldier Sculpture of the Royal Artillery Memorial. 2010. Photograph. ArtUK. https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/royal-artillery-memorial-265476.

War museums also contribute to different perceptions and emphases on how war should be remembered.

The 2002 West Point in the Making of America exhibition at the National Museum of American History, Washington D.C. featured WWI, but the conflict’s impact was not the focus.

Instead, the exhibition concentrated on the contributions of the US Military Academy West Point graduates’ personalities and contributions to American national development in economic and technological aspects.xv Therefore, the effects of WWI on the American nation and military personnel can be perceived as minimal or negligible.

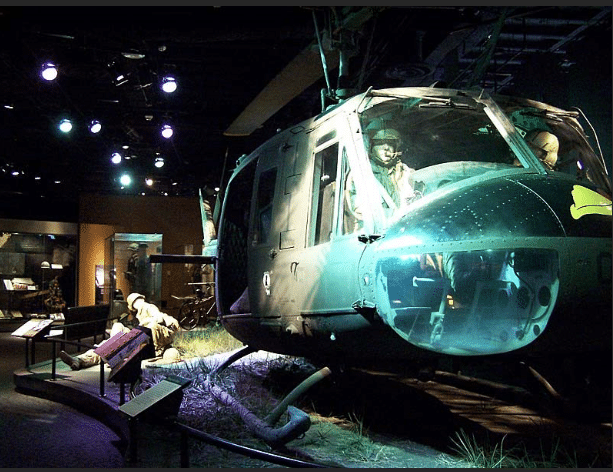

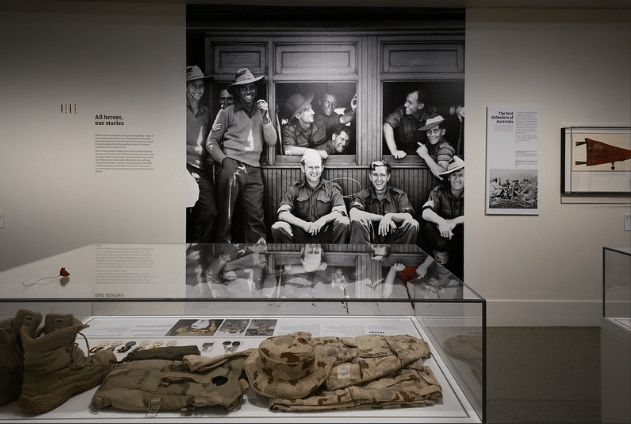

Prior to revamp efforts from 2009, the uniforms featured in the German Tank Museum were formal ceremonial uniforms that were not used in battle and were primarily from the officer ranks. This meant that uniforms worn during actual conflicts were not on display and present war in a fictitiously clean manner.xvi The permanent exhibition The Price of Freedom: Americans at War in the National Museum of American History explores the various conflicts the US has been involved in from the War of 1812 to the War in Afghanistan.

However, the focus on military weapons, equipment and uniforms of soldiers and other participants as seen in figure 3 arguably lead to lack of context and explanation for these diverse conflicts.xvii There are museum exhibitions like the 2008 In Memoriam: Remembering the Great War exhibition at the Imperial War Museum that incorporate anti-war aspects such as German artist Käthe Kollwitz’s woodblock etchings that criticised the negative impacts of WWI on mothers and children.xviii

However, this is not always the case as war museum artefacts and exhibitions are affected by curators’ preferences, community interests, pertinent issues and political considerations.xix Similarly to war memorials, the specific inclusions, exclusions and emphases of military conflicts in war museums create and justify specific views of wars.xx Due to these correlations, it is not surprising that war museums and memorials face similar questions on how and who decides on representations of war along with what is included and excluded.xxi A more thorough investigation of war museums’ effects on perceptions of conflicts is outside of the scope of this article, but it is important to examine the similar ways war monuments and museums shape specific views of war. This would allow for better understandings of how the unique textual, visual and design aspects of war memorials determine attitudes to wars.

Figure 3. Vietnam War Section of The Price of Freedom Exhibition. 2018. Photograph. National Museum of American History. https://americanhistory.si.edu/explore/exhibitions/price-of-freedom.

Truly Lest We Forget?

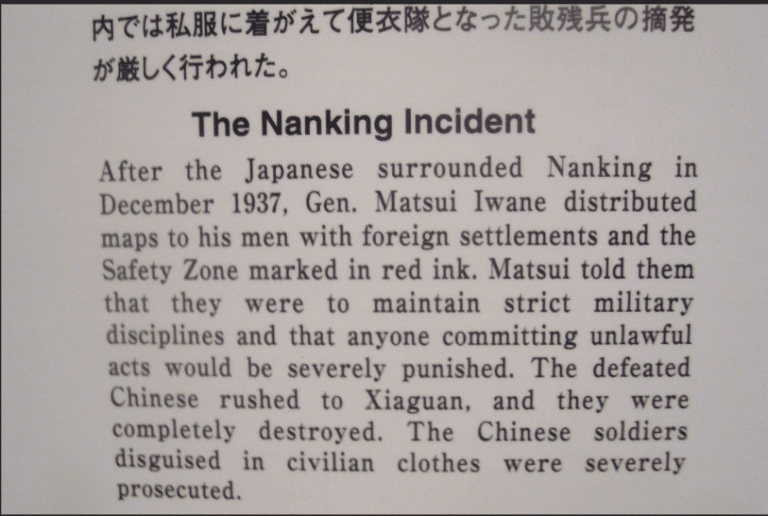

Despite the reflective nature of war memorials, not all wars or related events are remembered. The Australian War Memorial’s purpose in Canberra is to commemorate the sacrifice of all Australians who have died in war and aims to help Australians remember, interpret, and understand the Australian experience of war and its enduring impact on Australian society.xxii However, despite the Memorial’s role of commemorating wars fought by Australians, the various violent conflicts between colonial settlers and Aboriginal Australians known as the Frontier Wars (1788-1939) are not included in any visual or textual form in the Australian War Memorial.xxiii This creates arbitrary distinctions between the recognised sufferings of Australian soldiers and adversities of Aboriginal Australians in the Frontier Wars, along with legitimised forgetting that colonial warfare and violence were parts of the early history of modern Australia.xxiv Interestingly, the Veterans of Foreign Wars Memorial in Washington D.C. has no reliefs or inscriptions of the Mexican War and American Indian Wars, even though these conflicts contributed to large territorial expansions for the USA.xxv As with the Australian War Memorial, these omissions arguably reflect a deliberate willingness to forget particular wars because of these conflicts’ connections to lingering issues like colonialism’s repercussions and indigenous rights.xxvi Wars that are not popular like the Spanish-American War and the War of 1812 between the USA and Britain also have fewer memorials. It is therefore essential to recognise that a war’s significance as perceived in popular memory may not necessarily align with its true historical importance.xxvii Intentional forgetting is evident in criticisms of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum which does not talk about the violence instigated by the Japanese in different conquered areas like the 1941-42 Rural Pacification Campaign in China.xxviii Similarly, the Yasukuni Shrine in central Tokyo as seen in figure 4 does not mention the Nanjing Massacre by the Japanese of an estimated amount of 200,000 Chinese civilians and is recounted in a completely different manner.xxix These examples of absent war events indicate that some military conflicts are memorialised in ways to minimise discussions or representations of controversial war related issues for historical revisionism purposes or to move beyond questions of historical guilt. Therefore, what is commemorated is not always decided purely on historical merit, but on the popular memory, political and economic factors of different wars. xxx

Figure 4. Yasukuni Shrine Yushukan Museum Nanjing Incident Text Caption. 2016. Photograph. https://4corners7seas.com/?s=Yasukuni.

War monuments are designed to remember specific conflicts, but that does not mean every combatant or side is represented. For the Điện Biên Phủ battlefield where the French lost a major battle against the Viet Minh in 1954, Vietnamese memorialisation efforts do not reflect the French stories of war suffering and such remembrances had to occur in France, suggesting that war memorials and heritage can be biased towards the victors.xxxi Enemy combatants tend to be absent or depicted in symbolic forms to communicate positive messages of victory, visible in figure 5 where a defeated dragon is trampled by a female Victory figure in the Exeter War Memorial in Britain.xxxii This sort of imagery simplifies the nuances of the various factions of war into divisions of winners and losers or good and evil. The habit of reducing enemy combatants’ perspectives in war monuments is not just limited to historical conflicts. As a key event of the Global War on Terror (GWOT), the September 11th or 9/11 attacks are commemorated in various memorials with little attention to the Al-Qaeda terrorists or the act of terrorism that caused the loss of many lives.xxxiii While the erasure of the Al-Qaeda terrorists’ roles in 9/11 memorials could help with mourning and remembering the victims’ identities, there is a risk that the focus on emotional connections to the victims would overshadow visitors’ understandings of the contexts for terrorism and conflicts of the GWOT.xxxiv This danger of not fully understanding the complete situation of wars is also present in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum’s permanent exhibition where there is little detail about the rationale for the atomic bombs deployment by the American military leadership or larger WWII context.xxxv In the case of Hiroshima, the lack of information from the American viewpoint enhances a sense of innocent victimhood over questions of wartime responsibilities to the casualties and survivors of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. These omissions of certain combatants’ presences and perspectives reduce nuanced views of war and demonstrate that conflicts are not always remembered objectively for many war monuments.

Figure 5. Close-Up of Victory Female Figure of the Exeter War Memorial. 2016. Photograph. Imperial War Museums War Memorials Register. https://www.iwm.org.uk/memorials/item/memorial/2110.

Honour to All?

War exerts a significant influence on the societies it involves, but there is a tendency for combat or supporting military personnel to be the dominant subjects in war memorials. Although it is well-documented that many American women served on the US homefront through constructing military weapons in factories, war memorials have focused on soldiers and nurses.xxxvi Civilians caught between crossfires, the elites who managed wars, permanently mutilated individuals and grieving family members are rarely depicted.xxxvii The nuanced experiences of different groups affected by war like the grief of individuals who lost family members are sometimes made invisible through specific representations, like the deified Britannia figure from the Bridgend Memorial in Wales seen in figure 6 that presents a simplified image of a stoic British societal response to WWI.xxxviii The absence of complex and different impacts of military conflicts on society like disappointed or frustrated responses in some war memorials can lead to little room for critical views and contribute to nationalistic and meaningful narratives of wars. This is possibly the case with the lack of attention to the internment of many Japanese American civilians due to Japan’s enemy nation status and American government suspicions during WWII, with few specific museums like the Eastern California Museum dedicated to this controversial topic.xxxix Such contentious episodes are often not mentioned or acknowledged in WWII war memorials as it would undermine the narrative of WWII as the “good war” in American popular consciousness and hide WWII’s nuanced elements like shame and loss.xl The emphasis of combat and supporting personnel as subjects of war memorials can lead to imbalanced representations that reduce the presence of other affected societal groups or the questionable effects of wars.

Figure 6. Close-Up of Britannia Figure of the Bridgend Memorial. 2010. Photograph. ArtUK. https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/bridgend-war-memorial-323878.

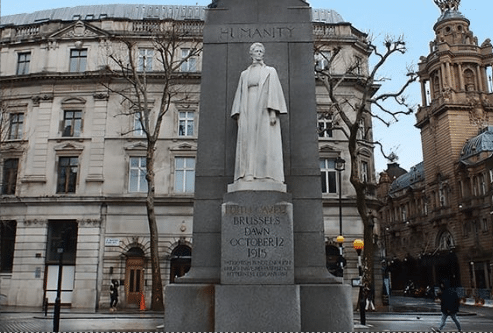

The tendency for war memorials to memorialise the names and efforts of those killed in battle can reduce attention to others who served in conflicts. War commemorative organisations like the Commonwealth War Graves Commission or CWGC which maintains the records and graves of individuals belonging to mostly former British Empire territories have been criticised for neglecting survivors of war through concentrating on remembering slain personnel in war.xli Although there are some memorials like the Australian Vietnam Veterans’ National Memorial in figure 7 which include the names of all combat or non-military personnel who either survived or died, this is not the usual practice for most war monuments and parallels questions about whether heritage institutions like museums can truly be inclusive for all.xlii In other words, many war memorials that only commemorate the war dead possibly create impressions that those who died in battle are the only ones worth remembering. Some memorials also create intentional or unintentional distinctions between who is deemed more important to remember. This is visible in the different commemoration efforts between two British female figures, Dr Elsie Inglis and Edith Cavell who both served as medical personnel in WWI. Dr Inglis established the Scottish Women’s Hospitals which aimed to get field hospitals in countries like Serbia, Russia and France. Unfortunately, she passed away of illness in 1917 and it was only in recent years there were efforts to produce a commemorative sculpture of her in Scotland. On the other hand, Edith Cavell was a frontline nurse who helped many British and French soldiers escape German occupied Belgium, leading to her capture and eventual execution. A memorial sculpture of Edith Cavell as seen in figure 8 was built promptly after WWI in 1920 at Trafalgar Square, London where many sculptures or busts of prominent British figures are placed. The contrasting memorialisation approaches to Dr Elsie Inglis and Edith Cavell raises considerations that only killed or executed personnel are deemed worthy of memorialisation.xliii The leanings towards commemorating the identities and deeds of those killed in battle over all who served in war could contribute to incomplete pictures and understandings of the impacts of military conflicts.

Figure 7. Australian Vietnam Veterans’ National Memorial. 2023. Photograph. National Museum Australia. https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/australian-troops-committed-to-vietnam.

Figure 8. Edith Cavell Memorial, Trafalgar Square. 2023. Photograph. National Portrait Gallery. https://www.npg.org.uk/visit/walking-tour/st-james-tour/stop-1.

The desire to remember soldiers killed in wars has led to a well-intended but problematic approach of a sense of equality among the slain. The Kranji War Memorial and Cemetery in Singapore contains killed Allied personnel that are buried in neat arrangements and with uniform tombstone designs visible in figure 9 due to the CWGC’s desire to symbolise the equality of service, sacrifice and comradeship across different classes for all soldiers who served in the British Armed Forces.xliv As the British Empire involved individuals from different cultures, religions and backgrounds, the CWGC did attempt to be sensitive to such aspects for war memorials under its care. For Kranji War Memorial and Cemetery, the CWGC incorporated Quran quotes for Muslim soldiers’ tombstone epithets and separate monuments for cremated Hindu Indian soldiers. xlv However, these attempts to be respectful of individual soldiers’ backgrounds was lost on local Singaporean visitors amidst the perceived dominance of British and Christian symbolism. A local Singaporean Muslim woman commented that the CWGC’s equality approach resulted in killed Muslim soldiers not being given the customary two headstones in Islamic funerary practices.xlvi A Singaporean Chinese visitor shared that the tombstones at Kranji were not done with Singaporean Chinese tomb designs or adherence to fengshui or traditional Chinese principles of achieving harmony with the environment.xlvii Although equal treatment of the war dead is commendable, it may not be reflective of cultural or religious elements of the deceased and their surviving relatives.

Figure 9. Kranji War Memorial and Cemetery. 2022. Photograph. National Library Board Singapore. https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-18/issue-2/jul-sep-2022/kranji-war-cemetery/.

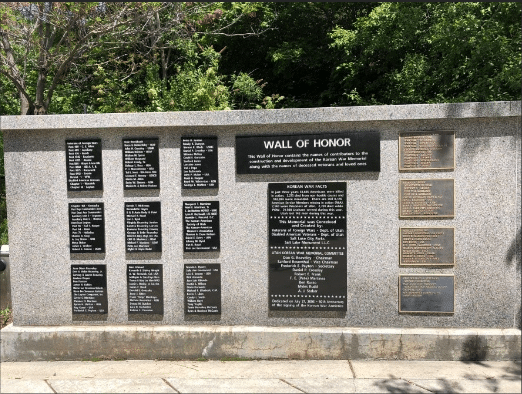

Another potential hazard of the individualised identifications in war memorials is the reduced attention to the contexts and reasons for wars. A special exhibition called For Country, For Nation at the Australian War Memorial as seen in figure 10 was held to celebrate and present the stories of Aboriginal Australian military personnel. Noteworthy examples like the first Aboriginal Australian officer Captain Reginald Saunders are shown but with no mention of the enduring racism he faced when he returned to civilian society.xlviii Similarly, For Country, For Nation constructs there was little racism in the Australian military like the Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit, the first unit with Aboriginal Australian soldiers. However, the exhibition does not detail the historical facts that they were paid a third of the usual Australian Army salary and went on strikes to protest this.xlix Without recognition of wider contexts or problematic aspects on individuals’ military careers, a complete picture of military services in war can be difficult to achieve. The focus on individualised identification could lead to little room for critical questions on the loss of human lives or political motivations of war as visible in the Salt Lake City Korean War Memorial shown in figure 11 where there was little consideration on why Communism appealed to many educated Koreans to fight the US.l The danger of war memorials is that they, like how museum exhibits could present seemingly fixed images that bury queries of contentious motivations and costs of war.li Many war memorials like the famous Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. do not refer to the causes of death of listed individuals, interesting when such memorials revolve around acts of violence.lii Although the prioritisation of naming individuals allows for personal connections with visitors, it potentially draws attention away from understanding the terrible aspects and motivations behind deaths and killings.liii The specific choices to remember and honour individual soldiers are meaningful, but contain possible dangers of minimising the less positive aspects or reflections on war.

Figure 10. For Country, For Nation Exhibition. 2016. Photograph. Australian War Memorial. https://www.flickr.com/photos/australianwarmemorial/albums/72157672888376494/with/31023260692.

Figure 11. Salt Lake City Korean War Memorial, Utah. 2023. Photograph. Korean War Memorials. https://koreanwarmemorials.com/memorial/salt-lake-city-ut-united-states/.

War with All its Glories, but None of the Horrors

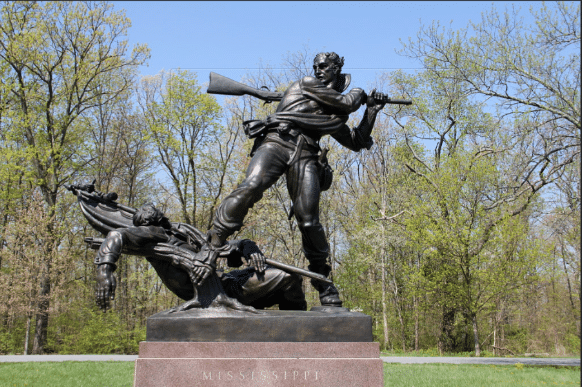

War is presented in a glorified manner through the idealisation of military personnel and death. Romanticisation is achieved through visual methods such as the usage of classical art styles for the Mississippi Memorial at Gettysburg National Military Park, USA depicted in figure 12 where a surviving athletic soldier uses his dead colleague’s rifle as a club. Even with the appearance of death through the killed soldier, the confident pose of the surviving soldier and his usage of the dead fighter’s weapon construct the deaths and sacrifices of the American Civil War as for a just political cause.liv Devastated cities, hunger, and physical mutilation are hardly present in British war memorials. Instead, religious symbols such as the cross are employed to link the sacrifices of soldiers with the profound meaning of Jesus Christ’s selfless act for all of humanity in Christian belief. lv This creates positive associations between death in war and nationalistic aspects like pride.lvi Figural sculptures or representations in war memorials arguably give visual forms of nationalistic ideals to viewers.lvii However, the idealised physical forms of soldiers like the Abertillery Civic War Memorial in Wales shown in figure 13 are contrary to historical photographs or accounts that showed many soldiers being malnourished and ill.lviii Although there are some war memorials that depict less triumphal heroic images of soldiers like Frederick Hart’s Three Soldiers statue in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington D.C., these representations still depict soldiers in a brave light.lix As there is usually no disclaimer of such historical inaccuracies, viewers might view these war memorials’ representations as authentic, similarly to how artefacts and artworks can be perceived uncritically as more important when placed in museums.lx

Figure 12. Itinerant Wanderer. Mississippi Memorial at Gettysburg National Military Park, USA. 2022. Photograph. https://www.flickr.com/photos/itinerant_wanderer/8703164472

Figure 13. Carl Nowell. Abertillery Civic War Memorial. 2018. Photograph. https://www.warmemorialsonline.org.uk/memorial/119055.

The presence or absence of textual elements can glorify soldiers in a simplified manner in war memorials. There are no details about the suspicions of Communist brainwashing that Korean War prisoners-of-war faced when they returned to the USA in the Salt Lake City Korean War Memorial’s inscriptions. Instead, the Memorial uses straightforward notions of honour and sacrifice to describe prisoners-of-war, which creates a very specific but not comprehensive historical interpretation of the Korean War.lxi Choi adds that such specific choices of war memorials do not capture the visceral realities of fighting and complex psyches of military conflict survivors, but potentially reduce war into fairy tale-like divisions of good and evil.lxii As not all war memorials contain explanatory textual elements to the extent as in museums, this could reinforce that what is visible is self-evident and accurate. Particularly since sculptures like the bronze figural sculptures of the Memorial of the Victims of Communism and Anti-Communist Resistance in Sighet, Romania creates an impression of unchanging historical interpretation.lxiii Heroic representations of military personnel and deaths in war memorials help to romanticise war for specific purposes like promotion of nationalism.

The Politics of the Living and the Dead

Despite their primary purpose of commemorating and remembering the dead, war memorials are influenced by the agendas and interests of certain living specific groups. Like other forms of heritage, war heritage is not natural but affected by the efforts and perspectives of actors involved in their development.lxiv This is noticeable in the opposing reasons to Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial design seen in figure 14 that were shared by Senator Jeremiah Denton and businessman Ross Perot, who felt that the design did not validate the Vietnam War as a noble cause.lxv From their points of view, this war memorial was not just about remembering the lives lost but to find some positive meaning from the American defeat in the Vietnam War.lxvi War memorials are then not only constructed to remember a specific conflict and its casualties, but to contribute to specific views in society. Ohio Congressman John Ashbrook expressed this intention in a letter to President Ronald Reagan that a new design other than Maya Lin’s design should be sought, which should be bright to redirect the opinions of the Vietnam War to one where fighting for freedom is a noble cause for young Americans.lxvii These deliberations on how to utilise war memorials to influence contemporary opinions are present in other countries like Australia, where the Australian Vietnam Veterans’ National Memorial committee document explicitly stated that symbolism between the Australian Vietnam Forces and ANZACs (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) of earlier conflicts such as WWI and WWII should be expressed in the design.lxviii This demonstrates a strong deliberate desire to accommodate the Vietnam War into the positive heroism of WWI-WWII ANZACs over specific historical period evaluations.lxix War memorial committees wield considerable influence over the designs of monuments. For instance, the committees overseeing the Llandudno War Memorial and Colwyn Bay War Memorial in Wales opted for designs featuring obelisks and a bronze figure, intentionally avoiding any explicit associations with the brutalities of war. lxx The impacts of war may be felt across different groups in society, but these examples demonstrate that the commemoration of war are heavily influenced or determined by specific actors.

Figure 14. Vietnam Veterans’ National Memorial. 2010. Photograph. The Cultural Landscape Foundation. https://www.tclf.org/landscapes/vietnam-veterans-memorial.

Debates about war memorial designs reflect important questions on whether representations of war can be decided by non-military individuals. Architects, sculptors and an art critic made up the initial Vietnam Veterans Memorial design jury which eventually selected Maya Lin’s design.lxxi However, as controversy over the design grew, the absence of any Vietnam War veterans in the design jury became a point of contention.lxxii This eventually led to the creation of an additional statue panel, made up of Vietnam War veterans.lxxiii Arguments about war memorials were not restricted to the decision-making bodies, but also about the designs. The Austin’s Military Order of World Wars wanted a traditional granite obelisk with a plaque bearing the names of killed servicemen in the Vietnam War.lxxiv The Austin memorial sculpture judging committee chose Thai art professor Thana Lauhakaikul’s Infinity of Life, a design where 98 eggs symbolised the fragility of life and number of killed soldiers.lxxv Unfortunately, this decision was viewed negatively by the Military Order of World Wars who found the association between eggs and dead soldiers ridiculous, leading to a dispute and subsequent agreement with the Austin Contemporary Visual Arts Association to do their intended sculptures separately.lxxvi Although these two cases ended with different results, it demonstrates that the contents and ideas of war memorials can be contested by military related individuals and groups if these notions are not deemed appropriate or relevant to military causes.lxxvii

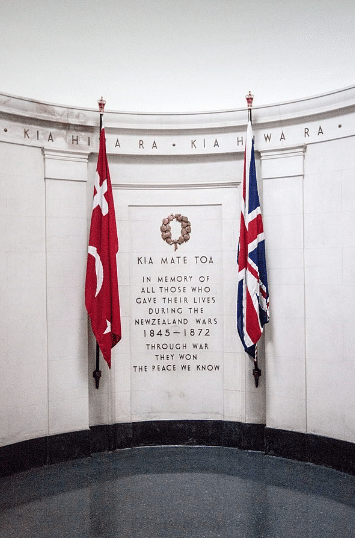

The construction and usage of war memorials serve as tools and obstacles for political diplomacy. Evident in the monuments built by other countries in Hyde Park, London, is the effort to build positive political ties. The Westminster Council, which manages Hyde Park worked in partnership with the Australian and New Zealand governments to commission and build monuments for WWI and WWII in Hyde Park.lxxviii Although the Council receives several monument proposals, it does not seek any public art that could shock or outrage any passers-by, meaning that it is unlikely that any memorials critical of war will be built there.lxxix The construction of the Australian WWII monument and New Zealand WWI and WWII monuments in figure 15 suggest that some of the war memorials constructed in Hyde Park were aimed at building good relationships, over historical relevance or importance.lxxx Cultivating positive political relationships through war memorials is also visible in the Vietnamese government’s claim that the land for the initially private French monument at Điện Biên Phủ was a gift in recognition of this battlefield’s mutual pain for both countries.lxxxi War memorials can also pose challenges in political relationships between nations, as evidenced by the protests and anger from China and South Korea over visits by Japanese politicians to the Yasukuni Shrine, where Class A war criminals like Prime Minister Tojo Hideki were clandestinely enshrined. lxxxii Australia’s decision to put the Gallipoli Peninsula, where its soldiers fought in WWI on its own National Heritage List outraged Turkey as it was viewed as an erosion of Turkey’s sovereignty and the relevance of Turkish historical perspectives of the site.lxxxiii These political uses and complexities of war memorials indicate that meanings of war memorials go beyond their respective chronological conflicts. War memorials, like museums have lofty and idealistic intentions of informing and educating the public. Unfortunately, they are not completely free from personal, professional, and political choices from different individuals. This is not to say that all war memorials are bad, but rather that more critical views and proliferation of war memorials with different views of wars can help produce better understandings of the various aspects of war.

Figure 15. New Zealand Memorial, Hyde Park. 2022. Photograph. New Zealand Ministry of Culture and Heritage. https://mch.govt.nz/nz-identity-heritage/national-monuments-war-graves/new-zealand-memorial-london.

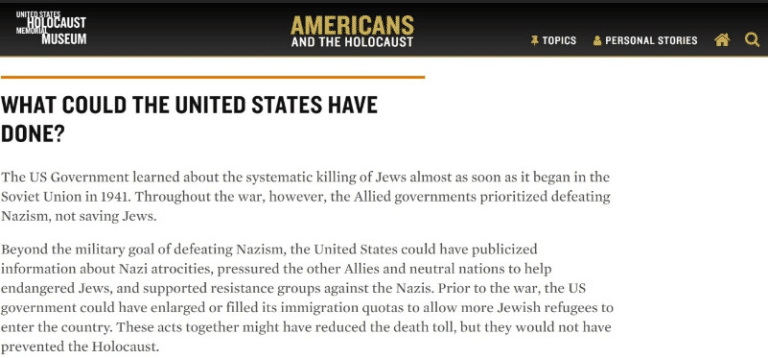

An ideal and unbiased war memorial appears to be an unachievable feat; however, particular war monuments demonstrate that it is an attainable goal. The Auckland War Memorial Museum in New Zealand has a large space recounting the 19th century New Zealand Wars fought between one faction consisting of the colonial New Zealand government and allied native Māori forces against another side made up of other Māori groups. Despite the New Zealand Wars resulting in the confiscation of several Māori lands and lingering issues about colonialism, the Auckland War Memorial Museum acknowledges this violent past through textual and visual elements.lxxxiv A dedicated memorial to the New Zealand Wars seen in figure 16 displays the flags of both the colonial government and anti-colonial government forces in an equal manner. In addition, the inscription commemorates the war dead of both sides of the New Zealand Wars. The Auckland War Memorial Museum attempts to incorporate artefacts and views from New Zealanders who remained at home to enemies like Japanese Navy pilot Sekizen Shibayama who piloted a Mitsubishi Zero on display in the Museum.lxxxv Although not perfect, the diverse ways the Auckland War Memorial Museum have integrated other or opposing sides’ perspectives are steps toward a more fair and objective war memorial. On the other hand, as seen in figure 17, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum provides avenues for critical questioning about whether America could have done more to prevent or reduce the Holocaust’s death toll. Interestingly, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum also confronts other difficult issues that would undermine the stereotypical positive image of USA’s role in WWII like the restrictive immigration policies that prevented more European Jews from escaping persecution and failure to bomb the railroads that led to the Nazi death camps.lxxxvi It is uncommon for countries to construct monuments and museums of war complexities and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s and Auckland War Memorial Museum’s approaches indicate that critical reflections and commemorations of wars are simultaneously possible lxxxvii

Figure 16. Szilas. Auckland War Memorial Museum Memorial Wall to the New Zealand Wars. 2016. Photograph. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Auckland_War_Memorial_Museum,_Memorial_Wall_to_the_internal_NZ_wars_2016-01-21.jpg.

Figure 17. Exhibit Section from Americans and the Holocaust Exhibition at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2021. Photograph. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. https://exhibitions.ushmm.org/americans-and-the-holocaust.

The commemorative, educational and mourning elements of war memorials mean that not all aspects of war like the violence of military conflicts or critiques are present. The exclusions of specific wars or episodes in several war memorials suggest that wars are remembered not purely for historical reasons, but also due to popular memory and political aspects. The absence of enemy combatant perspectives in war monuments demonstrate that commemorations of war do not reflect holistic and historical perspectives of war. Prioritised depictions of combat or supporting military personnel or the tendency to commemorate killed personnel can create imbalanced understandings of war’s effects on various societal groups. Individualised identification efforts in war memorials could lead to lack of attention to the nuanced backgrounds of military personnel or negative elements of war. War is romanticised through heroic images for specific purposes like cultivating nationalistic pride or historical interpretations. While the impacts of war may resonate across various societal groups, not everyone has a voice in determining how war is memorialised, as seen in the sway held by committees and pertinent interest groups such as veterans. War memorials are not restricted to their commemorated conflicts as expressed by the benefits and problems from political usage of war memorials. Despite the critiques of several war memorials, the incorporation of different views like enemies and promotion of critical questioning in the Auckland War Memorial Museum and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum indicate ideal objective war monuments are possible. War memorials, like museums have lofty and idealistic intentions of informing and educating the public. Unfortunately, they are not free from personal, professional, and political choices from different individuals. While there is much more to explore on this topic, the proliferation of diverse war memorials could potentially be advantageous by providing visitors with different perspectives and the freedom to interpret. 1

References

1. Abousnnouga, Gill, and David Machin. The Language of War Monuments. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

2. Auckland War Memorial Museum. “Scars on the Heart.’ Auckland War Memorial Museum. Published July 20, 2022. https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/visit/galleries/level-two/scars-on-the-heart.

3. Australian War Memorial. “Our Organisation.” Published March 16, 2021. https://www.awm.gov.au/about/organisation.

4. Bass, Jillian, “Memorial Craze: How War Memorials have been Changed by War.” Master’s Thesis, Chapman University, 2022.https://www.proquest.com/docview/2642946099?parentSessionId=vC%2Bblqx9HFyUmDT7kcF67ynJbwPI8ndOXE1N8LzSOTg%3D&pq-origsite=primo&accountid=12665.

5. Bonder, Julian. “Memory Works.” In A Companion to Public Art, edited by Cher Krause Knight and Harriet F. Senie, 25-29. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2016.

6. Cameron, Fiona. “Moral Lessons and Reforming Agendas: History Museums, Science Museums, Contentious Topics and Contemporary Societies.” In Museum Revolutions: How Museums Change and are Changed, edited by Simon J. Knell, Suzanne MacLeod and Sheila Watson, 330-342. Abingdon: Routledge, 2007.

7. Caso, Federica. “Representing Indigenous Soldiers at the Australian War Memorial: A Political Analysis of the Art Exhibition For Country, For Nation.” Australian Journal of Political Science 55, no. 4 (2020): 345-361. Doi: 10.1080/10361146.2020.1804833.

8. Choi, Suhi. Embattled Memories: Contested Meanings in Korean War Memorials. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2014.

9. Doyle, J. “Short-timers’ Endless Monuments: Comparative Readings of the Australian Vietnam Veterans’ National Memorial and the American Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial.” In Vietnam: War, Myth and Memory, edited by Jeffrey Grey and Jeff Doyle, 108-153. New South Wales: Allen and Unwin, 1992.

10. Duffy, Susan. “The Egg War.” Texas Monthly, (March 1980): 136-138. https://books.google.com.sg/books?id=Jy4EAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA136&lpg=PA136&dq=thana+lauhakaikul+infinity+of+life&source=bl&ots=uFF63rlmg1& sig=ACfU3U05tGRcmqS8eZM8Wz7WzimK1Vm3SQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjx5NnEqLr7AhXkzXMBHRbIAo4Q6AF6BAgIEAM#v=onepage&q=than a%20lauhakaikul%20infinity%20of%20life&f=false

11. Ehrenreich, Robert M., and Jane Klinger. “War in Context: Let the Artifacts Speak.” In Does War Belong in Museums? The Representation of Violence in Exhibitions, edited by Wolfgang Muchitsch, 145-154. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2013.

12. Gegner, Martin, and Bart Ziino. “Introduction: The Heritage of War: Agency, Contingency, Identity.” In The Heritage of War, edited by Martin Gegner and Bart Ziino, 1-13. Oxon: Routledge, 2012.

13. Hacker, Barton C., and Margaret Vining. “Military Museums and Social History.” In Does War Belong in Museums? The Representation of Violence in Exhibitions, edited by Wolfgang Muchitsch, 41-62. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2013.

14. Heffernan, Michael. “For Ever England: The Western Front and the Politics of Remembrance in Britain.” Ecumene 2, no. 3 (1995): 293-323. Doi:10.1177/147447409500200304

15. Lee, JongHwa. “The “Sacred” Standing for the “Fallen” Spirits: Yasukuni Shrine and Memory of War.” Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 9, no. 4 (2016): 83-98. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2016.1142597.

16. Logan, William, and N.T. Binh. “Victory and Defeat at Điện Biên Phủ: Memory and Memorialization in Vietnam and France.” In The Heritage of War, edited by Martin Gegner and Bart Ziino, 41-63. Oxon: Routledge, 2012.

17. Luke, Timothy W. Museum Politics: Power Plays at the Exhibition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

18. Mayo, James M. War Memorials as Political Landscape: The American Experience and Beyond. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1988.

19. Muzaini, Hamzah, and Brenda S.A. Yeoh. Contested Memoryscapes: The Politics of Second World War Commemoration in Singapore. New York: Routledge, 2016.

20. National Capital Planning Authority Canberra. National Memorial to the Australian Vietnam Forces: Conditions for a Two Stage Design Competition. Canberra: National Capital Planning Authority Canberra, 1989.

21. Raths, Ralf. “From Technical Showroom to Full-fledged Museum: The German Tank Museum Munster.” In Does War Belong in Museums? The Representation of Violence in Exhibitions, edited by Wolfgang Muchitsch, 83-98. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2013.

22. Reston, Jr, James. A Rift in the Earth: Art, Memory, and the Fight for a Vietnam War Memorial. New York: Arcade Publishing, 2020.

23. Romano, Gail. “The Zero: Two Men and a Plane.” Auckland War Memorial Museum. Published March 11, 2021. https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/discover/collections/topics/zero.

24. Senie, Harriet F. Memorials to Shattered Myths: Vietnam to 9/11. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

25. Seraphim, Franziska. War Memory and Social Politics in Japan, 1945-2005. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2006

26. Sion, Brigitte. Memorials in Berlin and Buenos Aires: Balancing Memory, Architecture, and Tourism. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2015.

27. Williams, Paul. “Memorial Museums and the Objectification of Suffering.” In The Routledge Companion to Museum Ethics: Redefining Ethics for the Twenty-First-Century Museum, edited by Janet Marstine, 220-236. Oxon: Routledge, 2011.

28. Winter, Jay. “Museums and the Representation of War.” In Does War Belong in Museums? The Representation of Violence in Exhibitions, edited by Wolfgang Muchitsch, 21-40. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2013.

29. Young, James E. The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

30. Ziino, Bart. “We Are Talking About Gallipoli After All.” In The Heritage of War, edited by Martin Gegner and Bart Ziino, 142-159. Oxon: Routledge, 2012.

Endnotes

1 Martin Gegner and Bart Ziino, “Introduction: The Heritage of War: Agency, Contingency, Identity,” in The Heritage of War, eds. Martin Gegner and Bart Ziino (Oxon: Routledge, 2012), 4. 2 Timothy W Luke, Museum Politics: Power Plays at the Exhibition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), xiii-xiv; Jeff Doyle, “Short-timers’ Endless Monuments: Comparative Readings of the Australian Vietnam Veterans’ National Memorial and the American Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial,” in Vietnam: War, Myth and Memory, eds. Jeffrey Grey and Jeff Doyle (New South Wales: Allen and Unwin, 1992), 127. 3 Julian Bonder, “Memory Works,” in A Companion to Public Art, eds. Cher Krause Knight and Harriet F. Senie (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2016), 29. 4 James E Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 3. 5 Harriet F. Senie, Memorials to Shattered Myths: Vietnam to 9/11 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 6. 6 Young, Texture of Memory, 3. 7 Bonder, “Memory Works,” 29; Senie, Memorials to Shattered Myths, 10. 8 Ralf Raths, “From Technical Showroom to Full-fledged Museum: The German Tank Museum Munster,” in Does War Belong in Museums? The Representation of Violence in Exhibitions, ed. Wolfgang Muchitsch (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2013), 84-88 . 9 Barton C. Hacker and Margaret Vining, “Military Museums and Social History,” in Does War Belong in Museums? The Representation of Violence in Exhibitions, ed. Wolfgang Muchitsch (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2013), 50-56. 10 Gill Abousnnouga and David Machin, The Language of War Monuments (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 92-93. 11 Robert M. Ehrenreich and Jane Klinger, “War in Context: Let the Artifacts Speak,” In Does War Belong in Museums? The Representation of Violence in Exhibitions, ed. Wolfgang Muchitsch (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2013), 145. 12 Ehrenreich and Klinger, “War in Context,” 146. 13 Abousnnouga and Machin, Language of War, 4; Young, Texture of Memory, viii. 14 Brigitte Sion, Memorials in Berlin and Buenos Aires: Balancing Memory, Architecture, and Tourism (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2015), 115-116. 15 Hacker and Vining, “Military Museums,” 56. 16 Raths, “From Technical Showroom,” 84. 17 Hacker and Vining, “Military Museums,” 56. 18 Jay Winter, “Museums and the Representation of War,” in Does War Belong in Museums? The Representation of Violence in Exhibitions, ed. Wolfgang Muchitsch (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2013), 32. 19 Young, Texture of Memory, viii. 20 Fiona Cameron, “Moral Lessons and Reforming Agendas: History Museums, Science Museums, Contentious Topics and Contemporary Societies,” in Museum Revolutions: How Museums Change and Are Changed, eds. Simon J. Knell, Suzanne MacLeod and Sheila Watson (Abingdon: Routledge, 2007), 334-335. 21 Winter, “Museums and the Representation,” 23. 22 Australian War Memorial, “Our Organisation,” published March 16, 2021, https://www.awm.gov.au/about/organisation. 23 Federica Caso, “Representing Indigenous Soldiers at the Australian War Memorial: A Political Analysis of the Art Exhibition For Country, For Nation,” Australian Journal of Political Science 55, no. 4 (2020): 346, doi: 10.1080/10361146.2020.1804833 24 Caso, “Representing Indigenous Soldiers,” 355. 25 James M. Mayo, War Memorials as Political Landscape: The American Experience and Beyond (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1988), 254. 26 Mayo, War Memorials, 254. 27 Mayo, War Memorials, 253. 28 Paul Williams, “Memorial Museums and the Objectification of Suffering,” in The Routledge Companion to Museum Ethics: Redefining Ethics for the Twenty-First-Century Museum, ed. Janet Marstine (Oxon: Routledge, 2011), 231. 29 JongHwa Lee, “The “Sacred” Standing for the “Fallen” Spirits: Yasukuni Shrine and Memory of War,” Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 9, no. 4 (2016): 381, doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2016.1142597. 30 Williams, “Memorial Museums and the Objectification,” 229. 31 William Logan and N.T. Binh, “Victory and Defeat at Điện Biên Phủ: Memory and Memorialization in Vietnam and France,” in The Heritage of War, eds. Martin Gegner and Bart Ziino (Oxon: Routledge, 2012), 60. 32 Abousnnouga and Machin, The Language of War Monuments, 106-107; 115. 33 Jillian Bass, “Memorial Craze: How War Memorials have been Changed by War” (Master’s Thesis, Chapman University, 2022), 6-7, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2642946099?parentSessionId=vC%2Bblqx9HFyUmDT7kcF67ynJbwPI8ndOXE1N8LzSOTg%3D&pq-origsite=primo&accountid=12665; Senie, Memorials to Shattered Myths, 4. 34 Bass, “Memorial Craze,” 73; Abousnnouga and Machin, Language of War, 2. 35 Williams, “Memorial Museums and the Objectification,” 231. 36 Mayo, War Memorials, 258. 37 Abousnnouga and Machin, Language of War, 115. 38 Abousnnouga and Machin, Language of War, 178. 39 Mayo, War Memorials, 259; 266. 40 Suhi Choi, Embattled Memories: Contested Meanings in Korean War Memorials (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2014), 87. 41 Hamzah Muzaini and Brenda S.A. Yeoh, Contested Memoryscapes: The Politics of Second World War Commemoration in Singapore (New York: Routledge, 2016), 97. 42 Doyle, “Short-timers’ Endless Monuments” 114. 43 Abousnnouga and Machin, Language of War, 169-172. 44 Michael Heffernan, “For Ever England: The Western Front and the Politics of Remembrance in Britain,” Ecumene 2, no. 3 (1995): 299, doi:10.1177/147447409500200304. 45 Muzaini and Yeoh, Contested Memoryscapes, 96; 100. 46 Muzaini and Yeoh, Contested Memoryscapes, 100. 47 Muzaini and Yeoh, Contested Memoryscapes, 100. 48 Caso, “Representing Indigenous Soldiers,” 356. 49 Caso, “Representing Indigenous Soldiers,” 356. 50 Choi, Embattled Memories, 83. 51 Mayo, War Memorials, 249. 52 Senie, Memorials to Shattered Myths, 4. 53 Bass, “Memorial Craze,” 7; Williams, “Memorial Museums and the Objectification,” 222. 54 Mayo, War Memorials, 176. 55 Abousnnouga and Machin, Language of War, 5; 97. 56 Abousnnouga and Machin, Language of War, 99. 57 Seraphim, War Memory, 233. 58 Abousnnouga and Machin, Language of War, 111. 59 James Reston, Jr, A Rift in the Earth: Art, Memory, and the Fight for a Vietnam War Memorial (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2020), 112. 60 Gegner and Ziino, “Introduction”, 4. 61 Choi, Embattled Memories, 90. 62 Choi, Embattled Memories, 93. 63 Williams, “Memorial Museums and the Objectification,” 226-7. 64 Gegner and Ziino, “Introduction”, 2. 65 Reston, Jr, A Rift in the Earth, xii. 66 Mayo, War Memorials, 170. 67 Reston, Jr, A Rift in the Earth, 105. 68 National Capital Planning Authority Canberra, National Memorial to the Australian Vietnam Forces: Conditions for a Two Stage Design Competition (Canberra: National Capital Planning Authority Canberra, 1989), 16 69 Doyle, “Short-timers’ Endless Monuments” 113; Reston, Jr, A Rift in the Earth, 117. 70 Abousnnouga and Machin, Language of War, 95. 71 Mayo, War Memorials, 201. 72 Mayo, War Memorials, 201. 73 Doyle, “Short-timers’ Endless Monuments” 113; Reston, Jr, A Rift in the Earth, 111. 74 Susan Duffy, “The Egg War,” Texas Monthly, (March 1980): 136, https://books.google.com.sg/books?id=Jy4EAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA136&lpg=PA136&dq=thana+lauhakaikul+infinity+of+life&source=bl&ots=uFF63rlmg1&sig=ACfU3U05tGRcmqS8eZM8Wz7WzimK1Vm3SQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjx5NnEqLr7AhXkzXMBHRbIAo4Q6AF6BAgIEAM#v=onepage&q=thana%20lauhakaikul%20infinity%20of%20life&f=false 75 Duffy, “The Egg War,” 136. 76 Duffy, “The Egg War,” 138. 77 Muzaini and Yeoh, Contested Memoryscapes, 109. 78 Abousnnouga and Machin, Language of War, 199. 79 Abousnnouga and Machin, Language of War, 198. 80 Mayo, War Memorials, 253; Abousnnouga and Machin, Language of War, 199. 81 Logan and Binh, “Victory and Defeat,” 48. 82 Seraphim, War Memory, 233; 282-283. 83 Bart Ziino, “We Are Talking About Gallipoli After All,” in The Heritage of War, eds. Martin Gegner and Bart Ziino (Oxon: Routledge, 2012), 156-157. 84 Winter, “Museums and the Representation,” 25. 85 Auckland War Memorial Museum, “Scars on the Heart,’ Auckland War Memorial Museum, published July 20, 2022, https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/visit/galleries/level-two/scars-on-the-heart; Gail Romano, “The Zero: Two Men and a Plane,” Auckland War Memorial Museum, published March 11, 2021, https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/discover/collections/topics/zero.